Now that we have defined clear fishery management goals, chosen performance indicators and reference values, developed harvest control rules, and assessed the current status of our fishery and stock(s) with the available data, we are ready to determine the best course of action to move our system closer to our goals. To improve the sustainability and climate-resilience of our fishery we need to choose harvest control measures (HCMs) that can effectively control fishing mortality, thereby improving stock health and system resilience. HCMs can be thought of as the specific management actions that are used to implement the Harvest Control Rules (HCRs) set at Step 8. So, for example, if an HCR set at Step 8 says to “reduce fishing mortality” if the results of our analyses reveal a specific combination of performance indicator measurements (as discussed in Steps 6 – 8), the corresponding HCM that we might put into effect in response to those measurements could be to “reduce fishing mortality by reducing the Total Allowable Catch for the year by X%.”

Note that in some cases the management guidance related to climate resilience goals and performance indicators (i.e., the last column in Step 8, Table 1) points to actions beyond the direct control of fishery harvests. For example, if assessments of climate resilience performance indicators indicates that stocks are beginning to shift beyond the jurisdictional boundaries of the fishery, the relevant management guidance might center on opening up a dialog with neighboring nations about how stocks can best be sustainably managed as they move across borders. Similarly, if assessments indicate that the mix of species in the area is beginning to shift as new species move in, old species move away, or both, management guidance might point to the need to increase fisher flexibility in terms of species they can catch and sell, which may require regulatory changes, gear shifts, and/ or market interventions. None of these things can be accomplished through the implementation of harvest control measures like catch or size limits. To help inform the development and implementation of such “out of the water” climate resilience-building management actions, see the tools and resources found in our Fishery Solutions Center toolkit.

There two main categories of harvest control measures (HCM): input controls and output controls (See Tables 1 and 2 below).

Input Controls:

Input controls are aimed at controlling fishing mortality indirectly, by reducing the efficiency with which fishermen can catch fish. They are often relatively easy to implement (because they require less monitoring, i.e. you don’t have to count all the fish that are caught), so they are often more appropriate for small scale fisheries that don’t produce much revenue (and hence have limited funding for monitoring and administration).

However, input controls may make it easier for fishermen to get around them, which works against the achievement of fishery goals. Input controls sometimes also cause other problems both ecological and socioeconomic in nature. For example, size limits are quite common in many fisheries but can result in discarding the undersized fish at sea to avoid prosecution, which in turn results in higher but undocumented fishing mortality, leading to overfishing. Gear restrictions such as a minimum mesh sizes are often used to prevent this, but if fishermen are motivated to maximize their catch, illegal gear is sometimes deployed resulting in catch of the prohibited size classes.

Other examples of input controls include: restrictions on engine horsepower, which can be circumvented by using multiple engines; restrictions on vessel size, which can be circumvented by increasing the number of fishing trips and the effectiveness of the gear; the implementation of fishing seasons, which can be rendered ineffectual by increases in fishing effort, either from existing fishermen fishing harder or from the entry of more fishermen; and spatial controls such as Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), which are often either too small to protect enough of the stock to control fishing mortality to a meaningful degree or so large that the boundaries are difficult to enforce. Good governance such as the allocation of secure catch or fishing territory privileges, including monitoring and accountability measures, can prevent these kinds of problems. In principle, any governance system that is very effective at controlling actual fishing effort and preventing gaming behavior (i.e., clever ways to get around the regulations) should enable adjustment of fishing mortality using input controls.

Output Controls:

Output controls, often called catch limits, directly control the amount of fish that are caught. They are generally more effective at controlling fishing mortality than input controls but are typically more difficult to implement than input controls because the fish have to be counted through one or various monitoring and/or catch accounting efforts. This can be challenging if fishermen land fish at multiple sites and/or discard fish at sea. Output controls can also be ineffective in a number of ways. For example, if catch limits are imposed on large groups of fishermen, it is very challenging to count the number of fish that are caught rapidly enough to ensure that the catch limit is not overshot, resulting in too much fishing mortality. If catch limits are imposed on individual fishermen and incentives to maximize catch persist, violations of the individual and aggregate catch limits (or “quotas”) can become commonplace, again resulting in too much overall fishing mortality. As is the case for input controls, output controls can also be made more effective through good governance (e.g., effective ways to hold fishermen accountable to catch limits, participatory decision-making processes, etc.) which generates incentives for fishermen to comply with the catch limit.

Step 11, Table 1. Description of common harvest control measures in fisheries. BMSY is the biomass associated with maximizing sustainable yield. FMSY is the fishing mortality associated with maximizing sustainable yield. SSB is the spawning stock biomass. (Table adapted from Liu et al 2016).

| Example Harvest Control Rule (HCR) | Type of Harvest Control Measure (HCM) | Method | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maintain BMSY/ Preserve Target SSB | Output Control | Catch Limit | Sets an upper limit on how many fish can be removed by a fishery in a given time |

| Escapement Threshold | Allows a certain number of fish to escape a fishery before harvest | ||

| Bag or Trip Limit | Limits the number of fish that can be landed by an individual fisher or vessel on a single day or fishing trip | ||

| Size Limit | Sets minimum and/or maximum bounds on the size of fish that can be legally landed in a fishery | ||

| Sex-specific Limit | Similar to catch limits, but broken down by sex within a target species | ||

| Fish at FMSY | Input Control | Temporal Limit | Restricts the time period over which a fish can be legally landed |

| Gear/ Vessel Restrictions | Restricts the dimensions and characteristics of a gear or vessel allowed to participate in a fishery. May also restrict the quantity of gears allowed | ||

| Deployment Limit | Places a cap on the individual fishers' use of fixed gears |

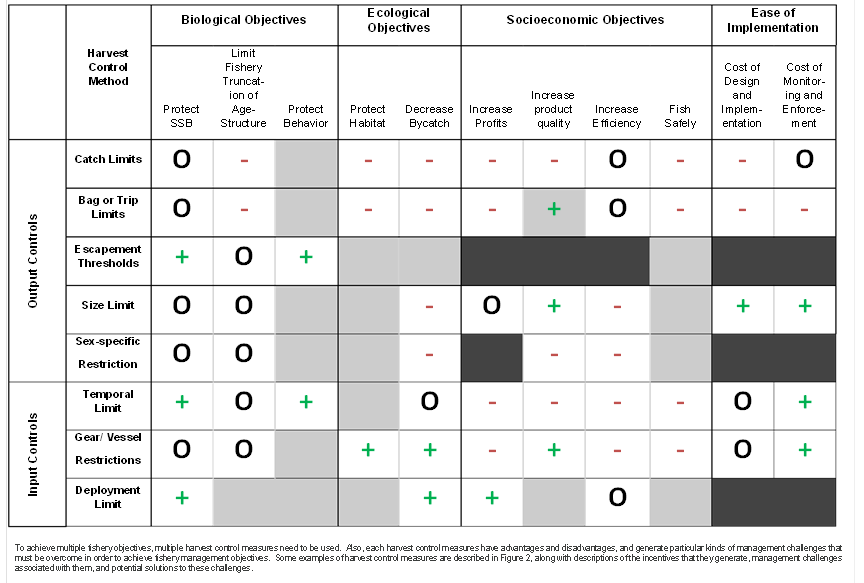

Step 11, Table 2. Harvest control control measures. Here we list the major types of fishing control measures that are used to achieve various kinds of fishery management objectives. The symbols indicate the degree to which each control measure is useful for achieving a specific objective.

Combining HCMs:

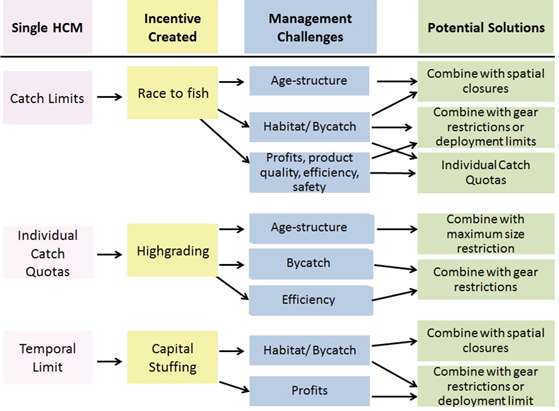

Harvest Control Measures (HCMs) can be combined to better achieve the goals of a given fishery management system. Figure 1 shows some common incentives and management challenges that may result from the application of a single HCM, as well as some potential solutions to those challenges, which often involve combining HCMs.

Most of the HCMs discussed above can be used in a multispecies fishery as well as a single species fishery; however, some measures may be more appropriate for multispecies fisheries. An important consideration in a multispecies fishery is the protection of “weak” or “constraining stocks.” These are the stocks that are in the poorest health, and/ or that have the highest vulnerability to the fishery, and which are thus at the highest risk of serial depletion. If weak stocks are valued fishery targets it may be that management measures are already being designed to catch these stocks sustainably. However, if they are not among the primary or most valuable targets and are perhaps just caught incidentally along with those targets, management may have to be more complex. If each stock in the multispecies fishery is managed with its own Total Allowable Catch (TAC) limit, for example, it may be necessary to close the whole fishery down when TACs for weak stocks are reached, even if there is TAC remaining for other species. Certain measures can be implemented to reduce the likelihood of a fishery closure for this reason, such as the creation of “risk pools” or programs where quota for weak stocks is shared among all the members of the fishery. See the EU Discard Reduction Manual for more guidance on these and other tactics to avoid depleting weak stocks and closing fisheries.

Harvest control measures that may be effective in multispecies fisheries include: Closed seasons, which can protect weak stocks if they are timed appropriately; closed areas, which can also protect weak stocks if they are sufficiently large and contain habitat suitable for/ critical to weak stocks; and sharing information on where weak stocks are concentrated, which can allow fishermen to avoid them as they pursue other targets.

In addition, it may be possible to make certain changes to the way the fishery is prosecuted, and/or to the management measures implemented, to help avoid serial depletion. For example, it may be possible for fishermen to adjust their fishing practices or gear such that weak stocks are caught separately instead of together with stronger stocks. For more information on this, please contact us and ask for the white paper, “Managing Multispecies Fisheries.”

Lastly, some tools have been developed to evaluate different management options in multispecies fisheries contexts. For example, the “Mizer model” is a multispecies size spectrum model in R that can be used to study the effects of different multispecies management strategies. Mizer projects species' size distributions, abundance, and yield by accounting for both fish population growth and predator-prey interactions, making this assessment a valuable asset to an ecosystem-based approach. With some modifications, Mizer can also provide a platform for evaluating the potential ecological and socioeconomic outcomes of different multispecies management scenarios, such as closed areas, fishing mortality limits on individual stocks, and fishing mortality limits on baskets of fish as well as the trade-offs between different management scenarios (see Step 6).

Fisheries management is always a dynamic process that must respond to fluctuations in environmental conditions, fishing behaviors, variable productivity of the resource, and changing market and economic conditions. Climate change is likely to make such fluctuations larger and result in new kinds of changes, such as shifts in species ranges and species composition. In addition, data- and resource-limited fisheries managers must often make management decisions in the face of data gaps that create uncertainties around the appropriate actions to implement, and the likely outcomes of those actions. In these fisheries it is therefore even more important to implement an adaptive management program that allows fisheries managers and stakeholders to re-visit fisheries goals, re-evaluate progress towards those goals, and re-examine the management measures that have been put in place to reach those goals based on new data, observations about fishery conditions, and learning from the outcomes of previous management decisions. Thus, we recommend going through the 11 Step FISHE process on a periodic basis – annually is recommended, but the appropriate period will depend on the individual patterns of the fishery and the target stock life cycles.

See the information and resources provided under the Collect More Data section of this website to learn about implementing and improving your data collection regime so that more and higher-quality data can inform each iteration of the FISHE process.